I take myself to see Dr. Janis,

my co-conspirator in eye care,

whose mother had the insightful idea

to spell her daughter’s name

as my mother spelled mine,

which is to say unusually

for a Janice.

How could I not find instant rapport

with a blonde, bespectacled Janis?

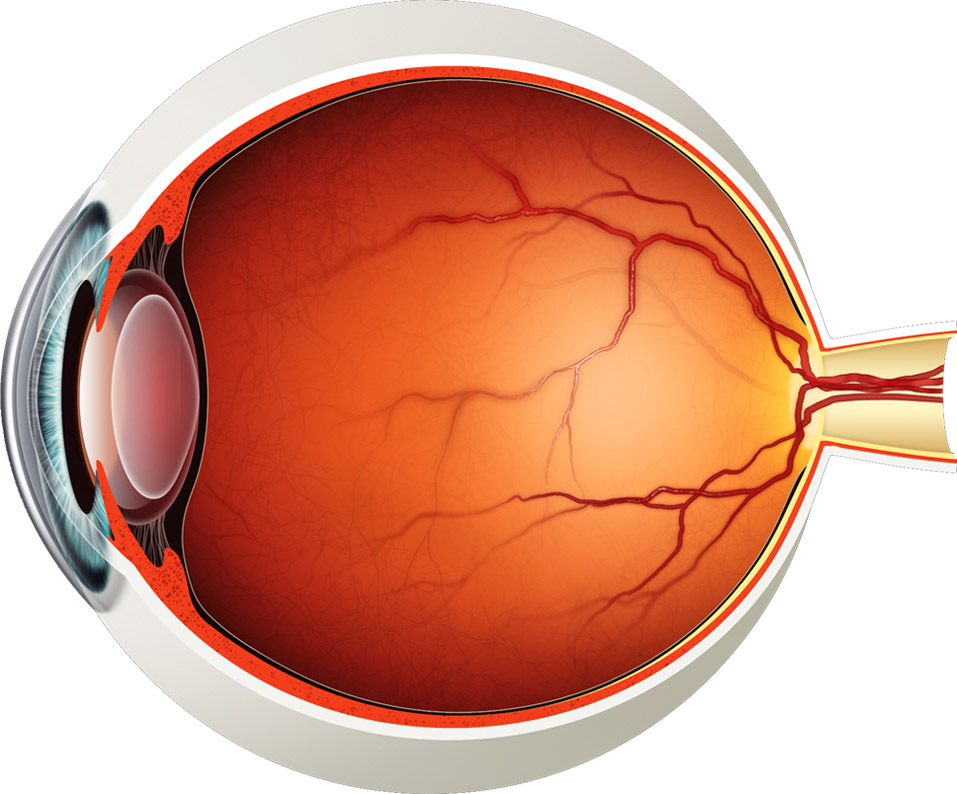

And even as my vision declines,

as her thoughtful eyes scan mine

through the big, bug-eyed machine,

I feel well seen.

Someday, should she have to deliver

the news—as another eyecare professional

had to tell my mother—that it is time

to stop driving, I will not be happy,

but I will understand.

I will not rage as my mother did,

unloading on her calm ophthalmologist,

as my mother sputtered, “But I can see!”

Never mind that, weeks earlier,

momentarily blinded by sun streaking

through the windshield, she’d driven

across the road and ended up

on the shoulder, stunned but not hurt.

I have a good idea what’s coming down

this bumpy road of macular degeneration

strewn with glaucoma. Every time I get

behind the driver’s wheel of my mother’s

former car,

I remind myself to not only look carefully

as I ease out of my driveway, or when I gently

pull out of parking spaces, but I also

offer prayers to the eye gods that I not

outlive my vision as my mother did.

Because there’s a world to see,

and I want to drink in every bit of it

with all the vision left in me.